Sociological interpretation of Liu Qiming’s “Red Envelope” and “Circle of Friends”

By Liao Liao

From human emotions to games: Liu Qiming’s “Red Envelope”

History, politics, and public issues have been the thread running through Liu Qiming’s artistic creations from beginning to end. While his earlier works were more of a projection of history and politics onto the artist’s personal psyche, starting with “Red Envelope,” the focus of his works no longer centers on the artist’s personal feelings, and Liu Qiming begins to explore the identity of the artist to explore the Internet and public space.

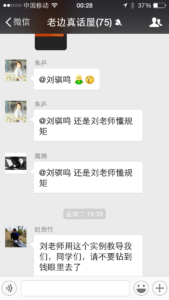

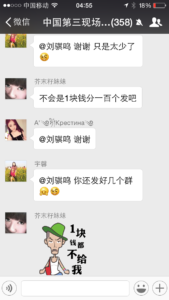

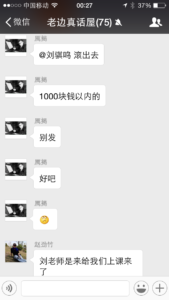

“Red Envelope” by Liu Qiming, Internet Behavior, Variable Dimensions, December 2014, WeChat Platform on Mobile Internet.

As early as 2014, when WeChat red envelopes were just launched, the artist sensitively captured the difference between the game nature of WeChat red envelopes and the human nature of traditional red envelopes, and realized the hidden Internet culture behind WeChat red envelopes.

Red envelopes are an indispensable part of Chinese festivals and ceremonies. From weddings and housewarming parties to birthdays and Chinese New Year, red envelopes assist and witness all major symbolic changes in life. It is somewhat like a gift in the West, but the emotion, relationship, and face wrapped in our red envelopes are Chinese culture that is difficult for Westerners to understand.

Chinese red envelopes are both like gifts and bonuses. Like gifts, red envelopes carry blessings and expectations but are not as personal and unique as gifts. Like bonuses, red envelopes are also real money, but we are not as pleased to receive red envelopes as we are to receive bonuses because we know that we are only temporary caretakers. The emotions, relationships, and face behind the red envelopes also dilute the satisfaction and contentment of cash in hand.

“The Red Envelope” by Liu Qiming.

Emotion, relationship, and face are everything in Chinese life. If we have ideals, then the ideal is to have thick emotions, broad relationships, and great face, and the important nutrient that nourishes this ideal’s growth is red envelopes.

There is no banquet that does not disperse, and there is no red envelope that is not used up. As an emotional lubricant for relatives and friends, a catalyst for weddings, new homes, and other ceremonies, and a tool for interest exchange, red envelopes contain not only cash but also Confucian ethical order, commercial culture’s mutual benefit, and the hierarchical order of power regulation. Red envelopes create, maintain, and strengthen Chinese interpersonal relationships.

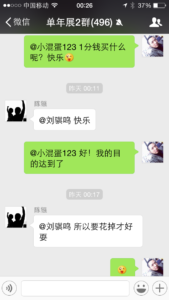

The “electronic red envelopes” launched by WeChat, Alibaba, and other platforms in the past two years are changing the definition of traditional red envelopes. In 2014, artist Liu Qiming created the work “Red Envelope.” On the WeChat red envelope platform, the artist shared 1 yuan with 100 people, resulting in interesting interaction and influence with these 100 participants. This work subverted the “emotion, face, and relationship” in traditional red envelopes. It neither allows the issuer to receive deeper emotional returns nor does it give him any face, as there is only one cent. A one-cent red envelope will not establish any interest relationship.

“The Red Envelope” by Liu Qiming.

The “one-cent electronic red envelope” uses the simplest method to reveal the cultural characteristics of the Internet: sharing, interaction, equality, and games. At the same time, the artist allows us to rethink the interpersonal relationship structure constructed by the “traditional red envelope.”

Liu Qiming’s “Red Envelope” hits the essence of “red envelope culture”. “One cent electronic red envelope” not only inherits the social function of traditional red envelopes, but also has no burden of human relationship debt, no expected return, and no short-term utilitarian purpose. It is just a spontaneous emotional expression and a voluntary gift. The giver and receiver of red envelopes in the game are equal in status and power, regardless of age or seniority.

“The Red Envelope” by Liu Qiming.

If traditional red envelopes revolve around human relationships, face, and connections, then the biggest principle of electronic red envelopes is fun and joy. The most important difference between electronic red envelopes and traditional red envelopes is that one is responsibility and the other is a game. Compared with the symbolic meaning and exchange value carried by traditional red envelopes, electronic red envelopes are more like a game. In the Internet age, red envelopes have transformed from a tool of obligation, human relationships, and exchange to an equal and relaxed collective carnival game.

Liu Qiming’s work “Red Envelope” may seem plain today, but two years ago, when WeChat red envelopes were just introduced, Liu Qiming was able to capture the subversion and deconstruction of traditional culture by WeChat red envelopes, and magnify the gaming characteristics of Internet culture in his work. This is the keen, sensitive, and agile quality that an artist must possess when focusing on public topics.

The Meaning of Images in Liu Qiming’s “Moments”

Liu Qiming’s “Moments” continues the artist’s consistent attention to public topics. As a contemporary artist, it is interesting to choose “images” from the WeChat Moments as the theme. In ancient times, literati paintings established a set of cultural elite aesthetics and ideal lifestyles through the creation, appreciation, exchange, and sale of images, thus isolating themselves from the common people. Today’s artists constantly share or repost various images in their WeChat Moments. The political news images shared by artists are no longer for building an aesthetic circle, but rather to obtain as much recognition as possible.

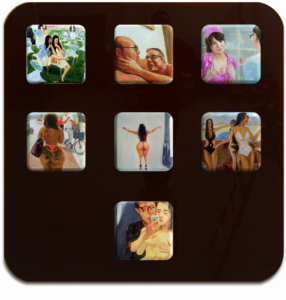

“Moments·Group NO.01” by Liu Qiming, oil on canvas, organic glass, 120x120cm, 2015.

“Moments” is not simply a collection of images. In fact, the work reflects various characteristics of images in the internet era.

The densely packed and layered images in the video collection of “Moments” show the scene where we are surrounded by images today. It implies that in the internet era, images have replaced words as the representation of the world and become the main rhetorical means for constructing public discourse space.

The images in “Moments·Groups” are fragmented and lack contextual explanation, symbolizing a characteristic of image dissemination: images exist independently of context and discourse. The way people think in the era of images is fragmented, disconnected, and two-dimensional, as opposed to the complex and coherent ideas represented by text.

“Moments·Group NO.02” by Liu Qiming, oil on canvas, organic glass, 120x120cm, 2015.

Liu Qiming selected images spread in “Moments” rather than those in the news media, expressing the role of images in consolidating consensus. People form a community of values and emotions through sharing images in their WeChat Moments, and images form a consensus and identity recognition among people with the same values. Images also serve as the glue of “Moments.”

When we see the massive amount of images presented in “Moments·Groups” on social media, we not only deeply feel ourselves surrounded by images, but also are reminded of another issue: images are more capable of stimulating our senses than words and language. In the face of the impact of massive images, watching becomes a direct visual stimulus and reaction. Faced with the visual impact of disasters and violent scenes time and time again, our hearts gradually become numb. The more we look at the brutal images, the more they seem like a simulated, safe, and exciting visual spectacle, gradually losing their impact and shock, and also eroding the meaning of the real events themselves. The massive images presented by artists remind us that we may treat image narration as instant consumption, while ignoring the profound essence behind the events.

“Moments·Group NO.03” by Liu Qiming, oil on canvas, organic glass, 120x120cm, 2015.

Liu Qiming also tried to depict the “images in Moments,” but Liu Qiming’s painting is not a simple repetition of photographs. Under the artist’s brush, various news images are transformed into somewhat crude, distorted, and unclear paintings. However, unlike Richter’s blurred treatment of characters in news photographs in his photorealistic paintings, Richter’s paintings reflect his ambiguous attitude towards political ideology as an artist.

Liu Qiming’s “photographic painting” implies that the real scene is transformed into photography, photography is then transformed into painting, and painting is then transformed into the audience’s understanding. In the process of several transformations, the meaning of the image may be distorted, misread, and misplaced, becoming increasingly blurry. The artist suggests the distant distance between “painted images” and real scenes. The artist uses painting to repeat the image, reminding us that images are not just real projections, but can also cause illusions, distortions, and fabrications.

Liu Qiming’s “Friends Circle Group” exhibition site.

刘骐鸣《红包》与《朋友圈》作品的社会学品读

文/廖廖

从人情到游戏:刘骐鸣的《红包》

历史、政治和公共话题是刘骐鸣艺术创作贯穿始终的线索。如果说以前的作品更多的是历史与政治在艺术家个人心灵上的投射。那么从《红包》开始,作品不再把重点放在艺术家私人感受之上,刘骐鸣开始艺术家的身份来探索互联网与公共空间。

早在2014年微信红包刚刚推出的时候,艺术家就敏感地捕捉到微信红包的游戏本质与传统红包的人情本质的区别,并且觉察到微信红包隐藏着的互联网文化。

▲ 《红包》 刘骐鸣 互联网行为 尺寸可变 2014年12月 互联网手机微信平台

红包是中国人的节庆和典礼上不可或缺的一环,从婚宴到乔迁,从生日到过年,种种具有象征意义的重大人生变化都有红包的助兴与见证。这有点像西方人的礼物,但是我们的红包里包裹着的人情、关系和面子,则是西方人难以理解的中国文化。

中国人的红包既像是礼物,又像是奖金。红包像礼物一样带有祝福与期待,但是又不像礼物那样富有个性而专属个人。红包与奖金一样都是真金白银,但是我们收到红包并不像收到奖金那样欣喜,因为我们知道自己只是临时的保管员。红包背后的人情、关系、面子也冲淡了现金在手的满足与踏实。

人情、关系和面子就是中国人生活的一切。如果说我们有理想,那么理想就是人情厚、关系广、面子大,而滋润这个理想茁壮成长的重要养分就是红包。

天下没有不散的宴席,天下没有散尽的红包。红包作为亲朋好友的情感润滑剂,婚礼、新居等仪式上的助兴催化剂,以及利益交换的工具,其中包着的不仅仅是现金,还有儒家文化的伦理秩序,商业文化的互惠互利,权力规训的等级秩序。红包创造、维持和强化着中国人的人际关系。

近两年的微信和阿里等发起的“电子红包”,正在改变着传统红包的定义。2014年,艺术家刘骐鸣做了《红包》的作品。艺术家在微信红包平台上,将1元钱分享给了100个人,与这100个参与者发生着有趣的互动与影响。这个作品颠覆了传统红包中的“人情、面子与关系”,既不会让发放者获得更深厚的人情回报,也不会让他面子有光,因为只有一分钱。一分钱的红包更加不会建立任何利益关系。

▲ 《红包》 刘骐鸣

“一分钱的电子红包”用最简单的方法,揭开了着互联网的文化特征:分享、互动、平等、游戏。同时,艺术家也让我们重新思考“传统红包”构建的人情、关系、面子的人际关系结构。

刘骐鸣的《红包》切中了“红包文化”的本质,“一分钱的电子红包”既继承了传统红包的社交功能,又没有人情债的负担,没有预期的回报,没有短期功利目的。只是一种发自内心的情感表达,一种自愿的赠予。发红包与收红包的人没有长幼尊卑之分,红包游戏中的地位和权力都趋于平等。

如果说传统红包围绕着人情、面子和关系做文章,那么电子红包的最大原则就是有趣和欢乐。电子红包与传统红包最重要的区别就在于:一个是责任,一个是游戏。相比起传统红包承载的象征意义与交换价值,电子红包更像一个游戏。互联网时代,红包由一种义务、人情与交换的工具,化身为平等、轻松的集体狂欢游戏。

刘骐鸣的作品《红包》在今天看来似乎平淡,但是在两年前,微信红包刚刚推出的时候,刘骐鸣就能捕捉到微信红包对传统文化的颠覆与解构,并且在作品中把互联网文化的游戏特征放大,这是一个关注公共话题的艺术家必须具备的敏锐、敏感与敏捷。

▲ 《红包》 刘骐鸣

刘骐鸣《朋友圈》的图像意义

刘骐鸣的《朋友圈》同样延续了艺术家一贯对公共话题的关注。作为一个当代艺术家,挑选朋友圈里的“图像”作为主题就非常有意思。古代的文人画通过图像(绘画)的绘制、欣赏、交换、出售来建立一套文化精英阶层的审美和理想的生活方式,以此与平民阶层隔离开来。而今天的艺术家则不停地在朋友圈里自发或转发各种图像,艺术家转发的时政新闻图像不再是为了建立一种小圈子的审美,相反是为了获得尽可能多的认同。

《朋友圈》并不是简单的图像的集合,事实上,作品折射着图像在互联网时代的种种特征。

《朋友圈》的视频集合里那些密密麻麻、层层叠叠的图像展示了今天的我们被图像包围的情景。寓意着在互联网时代,图像取代文字成为世界的表征,成为公共话语空间构建的主要修辞手段。

▲ 刘骐鸣 《朋友圈·群》展览现场

《朋友圈·群》的图片是呈碎片化的,没有上下文的说明。象征着图像传播的一个特征:图像脱离上下文和语境而独立存在。图像取代文字所代表的复杂而连贯的思想,图像时代的人们思考方式呈碎片化、断裂化、平面化。

刘骐鸣挑选的是“朋友圈”里传播的图像,而不是新闻媒体上的图像。表达了图像在传播中起到的凝聚共识的作用。人们通过在朋友圈内对图像的分享,形成一种价值与情感的共同体,图像在相同价值观的人之间形成一种共识与身份认同。图像也成为“朋友圈”的黏合剂。

当我们看到《朋友圈·群》中展示的海量的图像,除了深切得感受到自身被图像包围的情景之外,还提示着我们另一个问题:图像比文字和语言更能刺激我们的感官,在海量图像的冲击下,观看成为一种直接的视觉刺激与反应,面对一次次的灾难、暴力场景的视觉冲击,我们的心灵逐渐变得麻木。惨烈的图像越看越像一次仿真的、安全的、刺激的视觉奇观,逐渐失去冲击与震撼,同时也消解了真实事件本身的意义。艺术家呈现的海量图像提示着我们:我们可能把图像叙事当作即时消费,而忽略事件背后的深刻本质。

刘骐鸣还尝试描绘了“朋友圈的图像”,但是刘骐鸣的绘画并不是对照片的简单重复描绘。在艺术家笔下,各种新闻图像被转化为有些简陋、失真、面目不清的绘画。但是又与里希特的照相绘画的模糊性不一样,里希特的绘画里对新闻照片人物的模糊处理,反应了他作为一个艺术家对政治意识形态的模糊态度。

▲ 《朋友圈·群NO.04》 刘骐鸣 板面油画、有机玻璃 120X120CM 2015年

而刘骐鸣的“摄影绘画”意味着:真实场景转化为摄影,摄影再转化为绘画,绘画再转化为观众的理解,在几度转化中,图像的意义可能失真,可能被误读、错位,越来越模糊化,艺术家以此暗示着“绘画图像”与真实场景之间的遥远距离。艺术家用绘画来重复图像,提示着我们:图像不仅仅是真实的投射,也可能造成错觉、失真、造假。